- Home

- Tim Connolly

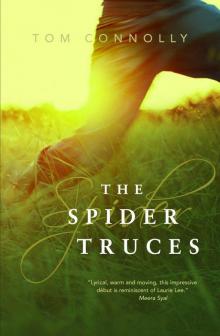

The Spider Truces

The Spider Truces Read online

In memory of Mark Bullock,

who would have been a great writer.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

AFTERWORD:

About the Author

Copyright

1

It was Great-aunt Mafi who told him that spider blood is blue. When that revelation made him feel queasy, she said that spider blood is blue the way the sea is blue when the sun shines. He liked that.

“That’s nice,” Ellis said. “That doesn’t give me the willies.”

And Mafi told him that when a spider dies its blood flows out of its body into the seas and rivers and lakes and that’s how the earth gets its water, but this only happens if a spider is allowed to die naturally, of old age.

Ellis’s dad told him he was more likely to be killed by a champagne cork than by a poisonous spider, but this didn’t have the desired effect.

“That’s no good! That’s just another thing for me to worry about! Champagne corks as well as spiders! You have to tell me something nicer, not something badder!”

His sister helped out too, reading from the encyclopaedia that spiders don’t get caught in their own webs because they have oil on their legs, so Ellis took to rubbing oil over his body in secret, every morning. At primary school he was known as Mr Sheen, due to the shiny appearance of his arms and face, and at home the diminishing stocks of cooking oil in the larder baffled Ellis’s dad as much as the discovery that soap could no longer form a lather on Ellis’s skin.

But of all the many discoveries Ellis O’Rourke made during the truces, his favourite was the first, that spiders give us the seas and rivers and lakes as their dying gift. He still thinks of the sea that way.

And it was Great-aunt Mafi who said to him, “Any day you see the sea is a good day.” This she said on the day she told him how his mum had died.

He sees the sea every day now. And he waits with a patience a young man should not yet possess.

Even here where it can be so bleak, the sea is often blood-blue, the sort of blue Ellis can fall into. From his rented house, he looks at the water. He loses focus and the water floods in; the image of blue fills his head and for a time that could be moments or hours he is nowhere. Free of thought. He barely exists. It is bliss. Like the mid-air moment of diving in.

The beach is a shingle peninsula. It heads to a point on the south-east corner. Ellis’s house faces due south across the Channel. It is the last building before the lighthouse and after that there’s the Point. Three hundred yards out to sea, on a sandbank, is the wreck of the Bessie Swan, a trawler that ran aground in June 1940, returning from Dunkirk with fifty men who waded to shore through waist-high water. You can’t wade out to the Bessie Swan nowadays. The Channel currents have gouged out ravines in the silt that are deep and treacherous.

On his first night on the beach, in the pub close by the lifeboat station, the old men had looked on without mercy as the young seasonal fishermen challenged Ellis to swim to the Bessie Swan and back. They marched him across the shingle, led by a callous and bloated-looking man in a black woolly hat, called Towzer Temple.

“You swim towards the steeple on the Marsh. The currents take you to the Bessie Swan.”

“If you swim straight for her, you’ll be in France tomorrow.”

“In a body bag …”

“Do it now and by closing time you’ll be back in the pub, a legend.”

“We’ve all done it,” said Towzer.

“It’s tradition.”

At the water’s edge, Ellis stared into the blackness and somewhere amongst the fishermen’s drunken voices, in which there was humour that Ellis was deaf to, he heard himself say, “But I’m only renting here …”

These limp words returned the men indoors, where the evening seemed impoverished and Ellis felt out of place. He began to wonder if they had been telling the truth, that they had all swum the ravines at one time or another, and they really did know best when they said he would be the greater for doing it.

The unfamiliar ceiling above his unfamiliar bed spun a little that first night and every single sound on the beach was new. As he waited patiently for sleep, Ellis noticed the glow of a cigarette at the open window and behind it the face of Towzer Temple, reddened by a map of fissured blood vessels. The fisherman leant easily against the sill, his elbows annexing a portion of the cabin-like bedroom, and as a wide grin disfigured his looks still further, he said, “It’ll bug you. You didn’t do it because you’re scared. And it’s going to bug you and bug you. Goodnight, Mr Only Renting. Sweet dreams.”

Money spiders populate the shingle and leave their egg sacs on the shore. Fishing boats line the beach and there’s a lifeboat station beyond them. Ellis likes to go shrimping north of the lifeboat, in shallow tides which scuttle in and out across the wide mud flats of the bay. He made a frame up last year, four foot by two. He wades out against the incoming tide, sweeping his net, and the frame makes a noise like distant music on a small box radio as it cuts through the water. He catches plenty, but could probably catch more if he knew more about it and didn’t get distracted by the far-away music.

Near the lifeboat station, the strip lights of the workers’ café pulse cold blue through the windows. Ellis usually goes there three or four times a week. People greet him but still don’t know his name.

At dusk, when the sky is angry, he heads out along the beach to the army ranges, then inland across the Backs where the shingle is carpeted with moss, and gorse surrounds the scattered lakes. A line of wooden posts betrays the route of a disused railway and beneath his feet he hears the thud of a sleeper encrusted in the ground like a dead bird. He imagines that he’s in Montana or the Australian outback or some other place he’s never been. He walks until his leg muscles burn. When darkness comes, a line of silver remains on the horizon and silhouettes the container ships, which turn to black. The winds rise up off the waves and tear across the peninsula and Ellis digs his feet into the shingle and allows the furious, thrilling gusts to pound against him like the souls of every man lost at sea. Furious souls or ecstatic souls, he is not sure which. Sometimes, he waits for hours. Patient. Devoted.

There is a line from a song his father once whispered to him and it plays in Ellis’s head as he returns across the flatlands to his unlit home. We must not go astray in this loneliness.

He moved here on Good Friday, 1989. A mist settled over the Point for a fortnight and the fog signal on the lighthouse boomed across the bay. He opened every door and window in the house and gave the spiders a few hours to move on without being harmed. The rooms gave up their mustiness to the salt air and Ellis felt the same excitement he had felt when he was a child.

So this is where that feeling has been hiding, he thought to himself.

At first he kept up his job, assisting a photographer called Milek, driving two hours to London. Then he worked a little less. Then he asked for a couple of months off.

“To clear my head, Milek.”

And that was a nearly a year ago.

This is another of those slow-motion mornings, Ellis tells himself. He wonders what time it is. He doesn’t wear a watch. Any that have been given to him over the years are gathering dust and he couldn’t tell you where. He thinks it through. He went out shrimping first thing and then he came back and the me

tal box was here on the dining table and then he’s been daydreaming. So it is probably late morning. He’s not idle and he’s not simple. It’s just a blissfully slow start to the day and he doesn’t use a watch. But, yes, he was shrimping first thing, he remembers clearly.

He can always tell if his sister has visited, and even though they are no longer good friends he likes the sensation of knowing she has been in. It means that Chrissie either saw her brother out on the flats and decided to leave him be or forgot to look for his silhouette in the silver bay. Either way, he likes the thought of her leaving him be or forgetting to look.

It is Chrissie who has left the metal box on the dining table. The box was once black but the paintwork is faded now and speckled by a slow rust. Ellis leans closer and looks down on the rust until it looks to him like a landscape photographed from a plane.

He’s in no hurry to open the box. He knows the contents exactly – he watched it being filled – and there’s nothing there of great significance. But for Ellis, having the box is almost like having his father back in the room and to feel his father nearby is the reason he moved here. Chrissie’s world doesn’t work that way. Dead means dead, and the inconsequential objects inside the metal box are the sorts of things that cannot combine to mean much to her. She wishes they could and that’s why it’s taken her a year to give Ellis the box. That’s why she has occasionally intimated that she might have lost it, an idea that gives Ellis butterflies because, although there is nothing particular in the box, all the pieces of nothing in particular belonged to Denny O’Rourke, and Denny O’Rourke was his dad.

If you rest your head against the metal box as if it is a pillow, and you close your eyes, and if your name is Ellis O’Rourke, then the crunching of shingle underfoot on the beach outside could be the sound of a spider perched on your shoulder eating a packet of crisps.

He opens his eyes and sees a woman walking. She puts down her bag, unfolds a stool and begins to sketch. A sparrowhawk hovers above the bushes where starlings and rabbits hide. Ellis listens to the wind piping around the lighthouse and watches as the woman with the sketch pad takes off her jacket. She is older than Ellis. Maybe twenty years older. He wants her to get into conversation with him, accept a cup of tea and sleep with him. He wants her to leave later that afternoon and there to be no talking. Only mute understanding. He would never tell anyone about her and would be able to get on with his life without the need for intimacy cropping up again for some weeks. He knows this is all wrong, but such thoughts are risk-free and a habit he’s fallen into.

The phone rings, startling Ellis. It’s Jed, his best friend.

“I have to tell you what I dreamt last night,” Ellis says immediately.

“I’m fine, thanks for asking,” Jed replies.

“Bear in mind,” Ellis says, “that I was two years old when man landed on the moon.”

“What?”

“And that I am not a particularly complicated person.”

“You are joking.”

“So how is it that last night I dreamt I was in the living room of the house in Orpington where I was born and my dad is there and my mum, but I can’t see her face, and we’re all gathered round the TV even though I’m pretty sure they didn’t have one, and my sister is just a pair of legs standing on the window sill holding the aerial up into the sky—”

“Wait! You’re getting detailed and weird. Let me get comfortable.”

Ellis waits as Jed lights a cigarette.

“I recognise some of the people in the room. There’s a few of the guys you and me knew on the building sites, and my Great-aunt Mafi is there pouring gin for everyone. Neat gin. The only historical inaccuracy is that it’s not Buzz Aldrin on the lunar surface with Neil Armstrong but Simon Le Bon. And the whole dream is in black and white, not just the TV screen. I look and see that to the left of me on the sofa is a young, unshaven, dark-haired man sitting with his girlfriend. And I realise as I look at this bloke that it’s that actor guy from Man About the House and Robin’s Nest—”

“Richard O’Sullivan.”

“Thank you. And I watch him in his studenty donkey jacket, smoking his cigarette and turning excitedly to his girlfriend, and I realise, My God! He doesn’t know he’s about to become the star of Man About the House and to be associated for ever with the greatest thing that ever ever happened on telly when we were kids, namely George and Mildred. He will be a part of that, and I know it and he doesn’t. Look at him! He’s just an aspiring actor watching the 1969 moon landing with his girlfriend and I know what’s going to happen to him in life and he doesn’t! I know he’ll never do Shakespeare or really crack that big screen role and that he will in fact be a sort of good-looking, understated Sid James. And do you know what it made me think?”

“I pride myself on not knowing what or how you think.”

“What else is there to dream? Being with my mum until I was four years old? How my dad was when she had gone? All the things that are somewhere in my head because I was actually there even though I was far too young to know it? It could crucify you! All this stuff locked away inside your head ready to appear in your sleep, it could bring your life to a standstill.”

There’s a long silence until Jed drags on his cigarette and says, “Your life is at a standstill.”

They go quiet. Jed is the one person who isn’t freaked out by Ellis going silent on the phone for minutes at a time. In fact, he considers such pauses a respite. Ellis lies back on the floor and wedges the telephone against his ear.

“You know why it’s at a standstill?”

“I’ve one or two ideas. What’s your version?”

“When I’m alone I dream of being with someone and when I’m with someone I wish I was anywhere else.”

“Ah, well, I’m glad you’ve brought that up because I have some answers for you,” Jed says kindly. “It’s because you are what we, in the outside world, technically term ‘an arsehole’. Private. Evasive. You’re a daydreamer and you keep all your best thoughts to yourself. People like me and the women you occasionally sleep with get the fag ends of your thoughts. If you didn’t make me feel so good about myself just by being you, there’d be nothing in this friendship for me. I am also willing to bet good money that when you are busy fucking the wrong people and wishing you were somewhere else, that somewhere else is wherever Tammy might be these days.”

“Out of bounds.”

“Why? What do you care if we talk about her?”

“I just don’t want to … except to say I was more committed to her than she was to me, before you slag me off.”

“Oh yeah, that’s right. I remember the evening you went away to America without telling her you were going. I remember that night thinking how ‘committed’ to her you were. Yeah, I reckon your decision not to even call her and say goodbye before fucking off to Iowa could easily have been misinterpreted as a proposal of marriage.”

This is why Jed is Ellis’s best friend.

“Fuck off.”

“Up yours.”

They each place the receiver down, gently.

Jed is right. When Ellis lies awake at night – in bed, or on the grass, or on the beach – he imagines that Tammy is lying beside him. He whispers sounds to her which are not quite words but are perfect for an imaginary love affair. He didn’t call her before he went away because it might have mattered to her that he was going but it might not and he didn’t want to risk finding out. And now two years have passed and he has left it too long.

He can’t understand why he feels so lost today. Or why he feels as if time is short when he has the whole of his adult life before him. He opens the metal box and it releases the smell of cherrywood fires in the cottage he grew up in. He sifts through a pile of photographs taken in the fifties and sixties of elderly relations he never knew, moves to one side a prayer card from his mum’s funeral in 1971, and picks up a passport-sized document which he remembers his dad showing him years ago. Denny’s name is written in ink on

the faded cover and beneath it are the words: Continuous Certificate of Discharge – Ministry of War Transport /Merchant Navy. Inside are five entries which map Denny O’Rourke’s career in the merchant navy, beginning in 1943, age sixteen, aboard the SS Papanui and ending in 1946 when his eyesight fell below acceptable standards for service. There’s a loose page inside, a temporary shore pass for Colombo Port, dated 15 November 1946.

My dad was twenty then, Ellis thinks. Two years younger than me.

He half closes his eyes and imagines being propelled across the sea, hugging the curvature of the earth, and arriving at Colombo Port. He sits there a while, in the heat, his image of the place indistinct and blinded by the sun. A wave breaks and he finds himself back home, listening to the shingle being dragged by its fingertips into the sea. It is a sound softened by its journey across the beach to Ellis’s house and it reminds him of the breeze that swept through the walnut trees on the morning his dad died. Joseph Reardon the farmer, who had been praying for Denny O’Rourke, told Ellis that the back door of the church flew open and a wind swept in at the exact time of Denny’s passing. Ellis doesn’t know what he thinks about that sort of thing but he does know that in the days and weeks that followed he and Chrissie received many letters and they sat shoulder to shoulder, knee to knee, silently passing them back and forth until their bodies came to rest against each other and he felt a surge of love for his sister which found no expression and would inevitably dissolve as the day wore on. Jed, whom Ellis had never seen hold a pen, wrote a letter; Ellis, your dad was one of life’s good blokes. Not all of us can say that. Be happy. Jed. Ellis showed Jed’s letter to Chrissie and she handed an envelope to him in return.

“Make sense of this,” she said. “Got it yesterday.”

It was a card from Dino, a Maltese guy Chrissie slept with on and off for six months when she was doing a journalism course in London. Dino had written: Dearest Spaghetti and Ellis, my condolences at your sad loss. Love Dino. And try as they might, Ellis and Chrissie could not begin to recall what cryptic, spaghetti-related episode or in-joke had occurred between them back then that Dino had clearly never forgotten.

The Spider Truces

The Spider Truces